These days, quite a lot of people have no idea who their neighbours are – their names, what they do, where they work etc, and the only interaction may be a quick ‘hello’, a nod, or occasionally collecting parcels from each other.

It’s just a sad sign of the times that as our lives become busier, and as families become more geographically spread, that we just don’t have the time or inclination to socialise with the people who live just a few feet away.

It’s not always been like this though – looking to the censuses of at least the early 1900s, you may discover that your ancestor’s neighbours play a much more significant role in your family.

‘Neighbours. Everybody needs good neighbours’

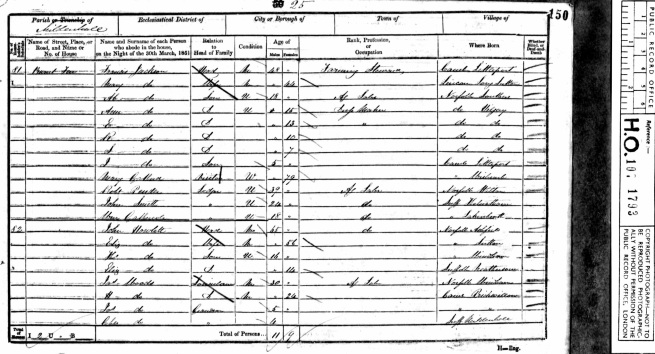

When the 1861 census took place, the enumerator for Swaffham Bulbeck in Cambridgeshire, England, visited Village Street and noted down the names and details of everyone there including four families who were all living nextdoor to eachother – each with different surnames.

The enumerator may well have known the Newman, Skeels, Fordham and Levitt families seen in the example above, but the census does not shed any light onto the significance of the proximity of these 18 people.

The 18 people on this census folio are actually four generations of the same family, and this folio is a snapshot of how they had stayed together as the families grew. By trawling back to the 1851 census, you are able to find the core family again, in a much smaller family group.

The seventy-seven year old widow, Elizabeth Skeels, née Richardson, is the great grandmother and matriarch of the family. She appears here in 1861 as living just feet away from her daughter’s (Elizabeth Levitt, née Skeels) family, and is surrounded by the families of her daughter’s oldest children (Emma Newman, née Levitt and Harriet Fordham, née Levitt) whilst the younger children are still at home.

At first glance, I would have spotted Skeels, or if i had been in Newman or Levitt ‘research mode’ I’d have seen them and not necessarily spotted or realised the importance of the families around them.

So, keeping an eye on what’s happening nextdoor on the census returns can help you in your research.

Four families in a row is probably my best when it comes to related neighbours – can you beat that? Or have your ancestors had a famous/infamous neighbour? Let me know in the comments below.